Back to square one

Site-specific installation

Variable size

2023

(KAIR 2023)

インスタレーション

サイズ可変

2023年

(神山アーティスト・イン・レジデンス)

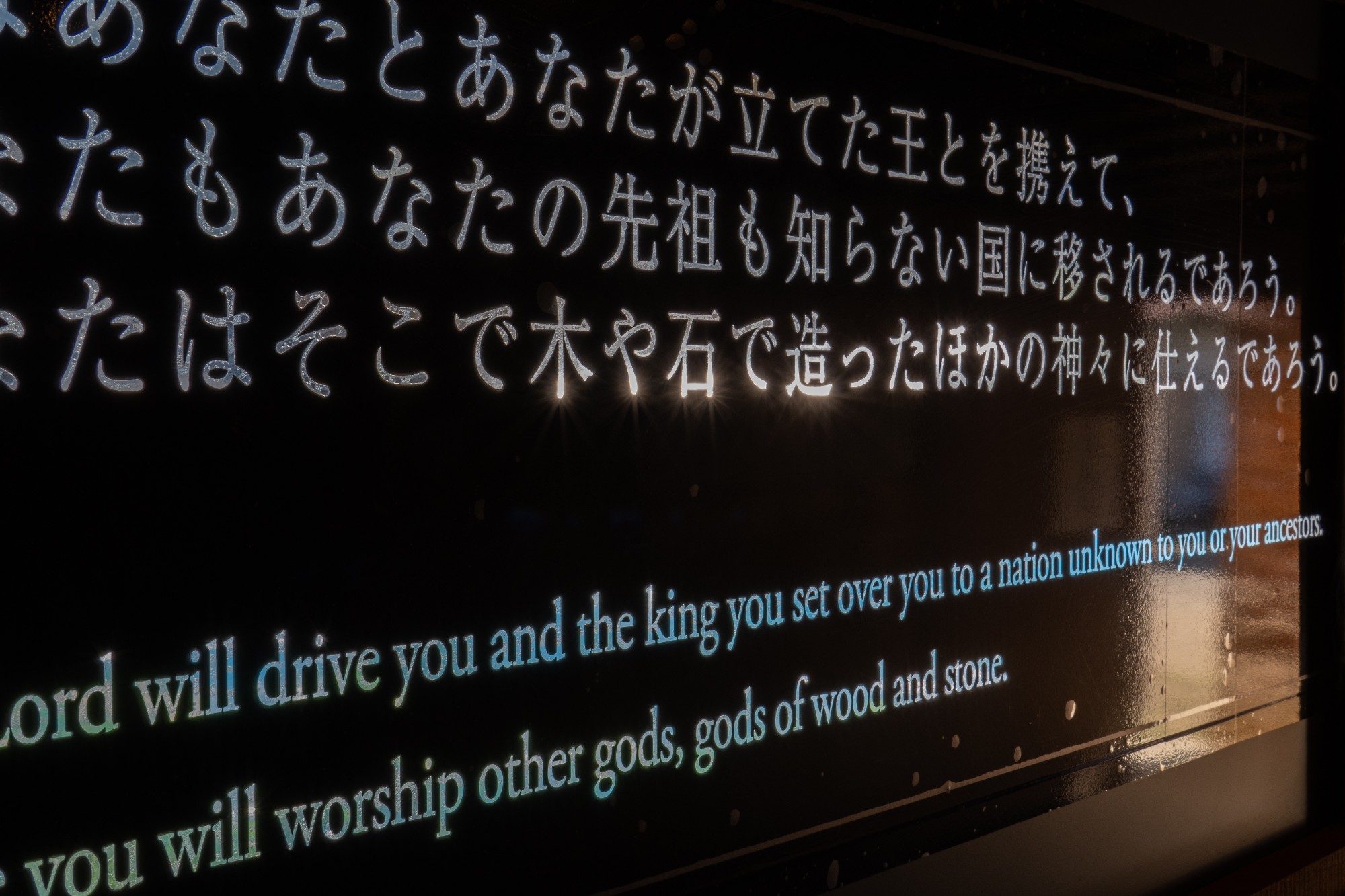

How did people begin to have writing?

Or, why did people need writing?

Writing came to Japan around the transition from the Jomon period to the Yayoi period, from around the 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD. There are no signs of any large battles occurring during the Jomon period, and it was a very peaceful and stable period that continued for over 15,000 years. Signs of battles begin to appear around the Yayoi period, when a ruling system to create a country began and tribes began to fight one another.

The appearance of writing seems to have facilitated the appearance and forming of nations (cities and empires), the uniting of people by ranking them into classes, and the exploitation of humans. What was the background to this dramatic change? In order to confront this simple question, I use place names and ruins that remain in various locations, walk the area myself, look with my own eyes, observe, and think. Then I use my hands to create some kind of shape. That shape is something you could call a hypothesis, or you could call it an artwork.

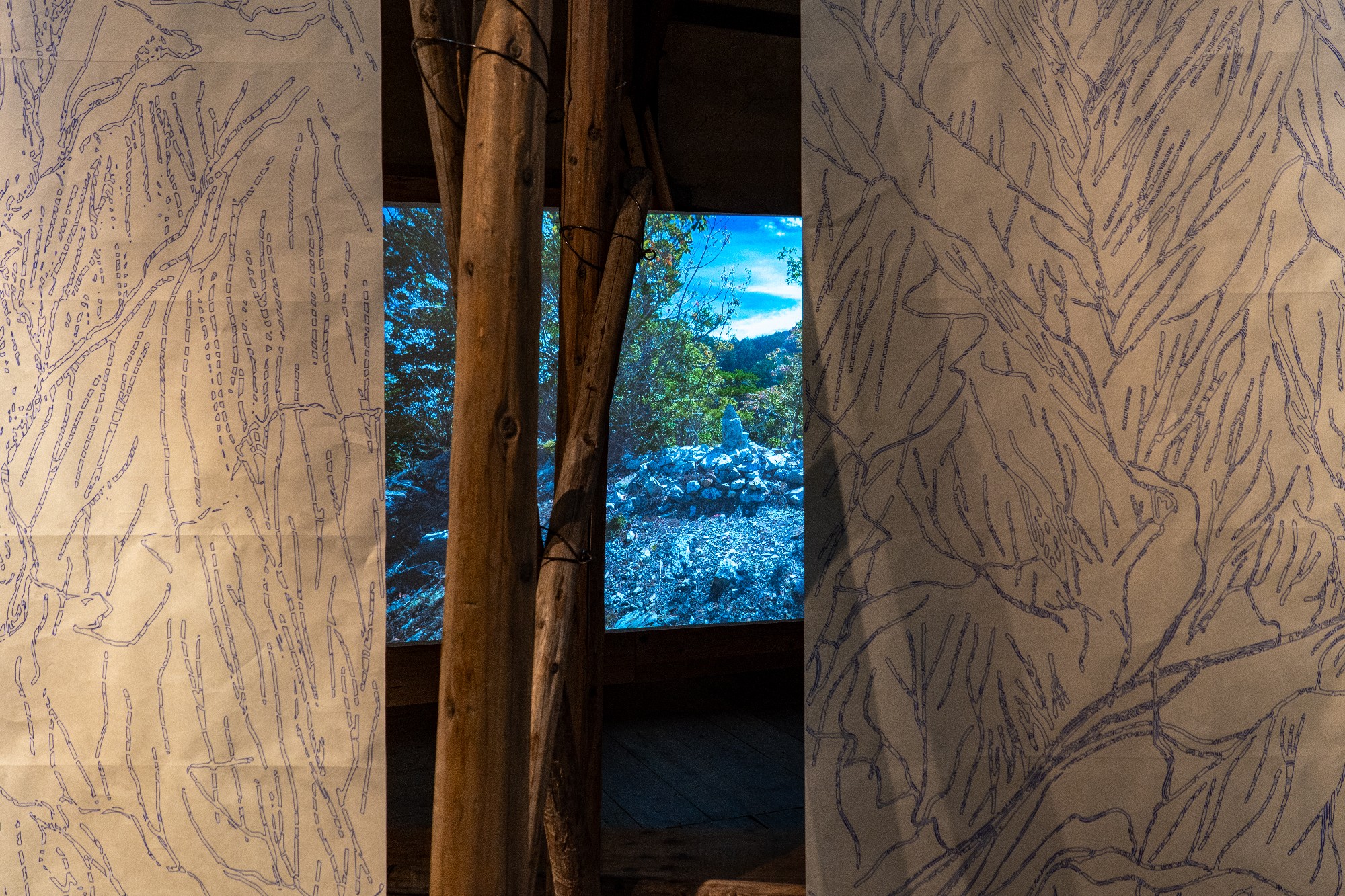

Kamiyama is surrounded by mountains, and about 83% of the area is mountainous. The small amount of flat land is mainly lowlands with the Akui River in the east and its tributaries, with gently sloping land due to river terraces and landslides. Looking at a map of Kamiyama, the steep mountains have been uniformly eroded by the Akui River and its tributaries, but in two places there is a different characteristic terrain than the surrounding area. One is a hill in the area around where a tributary joins the Akui River, created when a meander was cut off due to erosion and formed a shortcut. Another is north of Asahimaru where a gently sloping area opens up suddenly on a steep mountainside. The former is the location of Kamiichinomiya Oawa Shrine on Mt. Oawa, and the latter is the location of Higanji Temple.

I thought there must be something here, and this year in June I came to Kamiyama for a preliminary visit. I learned that Kamiichinomiya Oawa Shrine enshrines the goddess Oogetsuhime, who brought the abundance of five grains, and Higanji Temple has a legend that it is the site of the ancient ruins of Himiko’s castle. I felt without a doubt that those two places have some connection, without any concrete evidence other than my intuition, and began a journey of tracing the activities of the ancient people and their vestiges.

In Tokushima prefecture, there are many remains of ancient rituals and worship in the form of giant boulders or piles of countless smaller blue rocks. It’s possible to trace the change in the architectural form of shrines as they merged with Buddhism when it was introduced from the continent. Many of these shrines are listed in the Engishiki Shinmyocho which was compiled in the Heian period and are connected to the gods that appear in the Kiki legends. I was surprised to discover that there are shrines said to be the original sites of such famous shrines as Suwa Taisha and Izumo Taisha.

Conflict, negotiation, and cooperation between the people who lived on the steep slopes of Mt. Tsurugi where spring water is abundant, and the people who lived along the Yoshino, Akui, and Naka rivers and their tributaries which brought the blessings of the mountains. That shape gradually built up, mixed, blended, and gradually, and sometimes violently shaken, continuing to the present day. I suppose in the background of this is the rice plant. I arrived at that one drifting point during this journey.

The rice plant, compared to other types of grain, has high yield and high nutritional value. Rice can be stored, and in turn, wealth can be stored. Rice cultivation brought technology for making bronze and ironware. In order to harvest rice, the topography and waterways must be manipulated and managed. A lot of manpower must be harnessed. The civil engineering and ironwork technology used in rice farming becomes military power in times of war. People come together and reliably harvest rice and build wealth. In other words, building a nation means growing rice, and I believe that growing rice necessarily creates conflict, negotiation, and cooperation.

The title of my exhibition, Back to Square One, comes from the old children’s board game, Snakes and Ladders, that is mainly played in Europe and North America. Snakes eat creatures that destroy rice crops such as frogs and mice, so they are sanctified. The shimenawa decorative ropes seen in shrines are said to be a representation of a snake. In Snakes and Ladders, snakes and ladders are positioned on a grid, and if the player’s piece lands at the bottom of a ladder, it can climb to the top of the ladder, but if it lands on the head of a snake, it must go back down the course to the location of the snake’s tail. Players can make progress by rolling a dice and moving forward the number of spaces indicated on the dice, make leaps forward with a ladder, or go backward after being caught by a snake. My journey at KAIR had many instances like this act of going forward and back, moving towards the goal, and going back to square one.

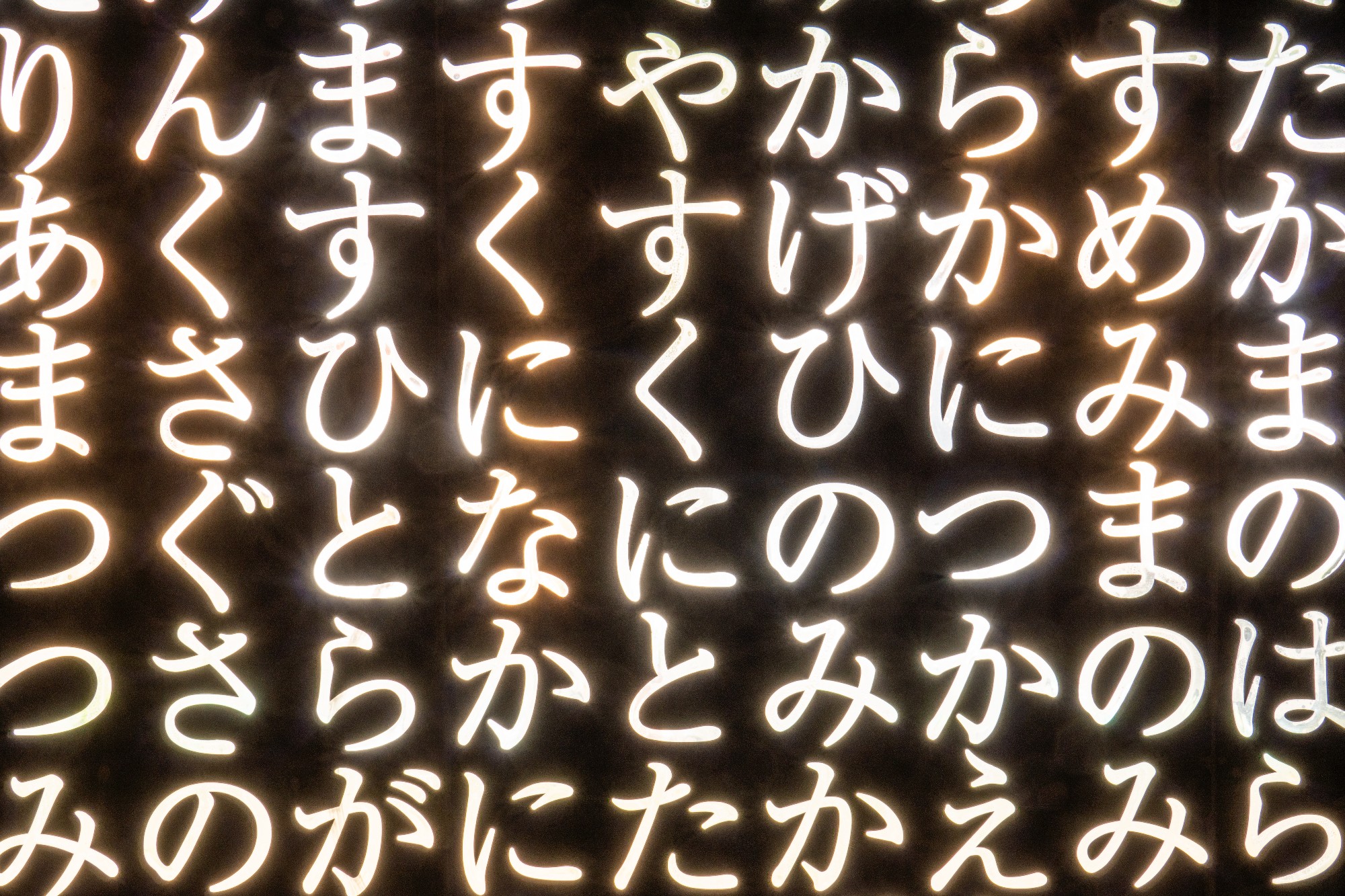

I used the unique characteristics of Yoriiza, a former theatre that was used as a place for entertainment in the town, making my work with an interweaving of video, structures and sculptures, drawings and collected objects. It’s a sort of hypothesis where local legends and folklore are recalled, overlapped, and reconstructed, or it could also be a stage set that allows people to experience traces of my walking, looking, observing, learning, and making.

人々はなぜ文字をもつことになったのだろうか。

あるいはなぜ文字をもたなければならなかったのだろうか。

日本に文字が伝わったのはちょうど縄文時代から弥生時代に移行する頃の紀元3世紀ごろ、遅くとも紀元後1世紀ごろだとされている。縄文時代には大きな争いの形跡もなく、とても平和で安定した時代が15,000年以上も続いた。国をつくるという支配体制が生まれて部族間の争いの形跡がみられるようになったのは弥生時代あたりからだという。

文字の出現は、クニ(都市や帝国)の出現と形成、人々を束ねる階級への位付け、人間の搾取に便宜を与えたようにもみえる。その劇的な変化の背景には何があったのだろうか。わたしは、そんな素朴な疑問に向き合うべく、各地に残る地名や史跡を手掛かりに、自ら歩き、自らの目で見て、観察し、考察する。そして手を動かし、なんらかの「かたち」をつくる。その「かたち」は、その時点におけるわたしの「仮説」と言えるかもしれないし、「作品」とよばれるものなのかもしれない。

神山町は周囲を山々に囲まれ、全面積の約83%が山地であり、残りのわずかな平地は、東に開かれた鮎喰川とその支流域のわずかな低地、河岸段丘や地すべりによる緩傾斜地にある。神山町の地形図をながめていると、急峻な山々が鮎喰川とその支流域によって全体的に均一に浸食された様子が見て取れるが、2カ所ほど周囲とは異なる特徴的な地形がある。ひとつは鮎喰川とその支流が合流する付近にある還流丘陵と思われる蛇行した流れが浸食などで流路がショートカットされてできた丘陵。もうひとつは旭丸から北の急峻な山腹にぽっかりと開けた緩傾斜地である。前者は上一宮大粟神社のある大粟山、後者には悲願寺がある。

私はここには何かあるに違いないと思い、今年の6月に神山に下見に訪れた。上一宮大粟神社には五穀をもたらした豊穣の女神とされる大宜都比売(おおげつひめ)が祀られ、悲願寺には卑弥呼の古城跡という伝承が残っていることを知った。このふたつの場所には何かつながりがあるに違いない、というなんの根拠もない直感から出発し、古代の人々の営みとその痕跡をたどる旅が始まった。

県内には、巨石そのもの、あるいは無数の青石を積んだだけの形態をした古代の祭祀・崇拝形式の遺構が数多く残り、大陸から伝来した仏教と和合しながら形成されていった神社の建築形式の変遷を辿ることができる。そしてそれら神社の多くが、平安時代に編纂された延喜式神明帳に記載されており、記紀神話に登場する神々と連続的に繋がっていること、そしてさらに諏訪大社や出雲大社といった有名神社の元宮とされる神社が揃っていることを知り、驚いた。

剣山系の湧水が豊富な急峻な山々に棲みついた人々と、山々の恩恵をもたらす吉野川、鮎喰川、那賀川とその支流沿いに棲みついた人々との衝突、交渉、協働。その「かたち」は、徐々に蓄積し、混ざりあい、和合しながら、ゆるやかに、ときに激しく揺さぶられながら、現在までつながっている。そしてその背景には「イネ」があるのではあるまいか?これが今回の旅で辿り着いたひとつの漂着地点である。

イネは、他の穀類と比べて収量が多く栄養価も高い。コメは備蓄することができ、富が蓄積されるようになる。稲作は、青銅器や鉄器製造の技術をもたらした。コメを安定的に収穫するためには、地形と水脈を操作・管理しなければならない。多くの労働力を確保しなければならない。稲作に用いる土木技術や鉄器は、戦になれば軍事力になる。人をたばねて安定的にコメを収穫し、富を備蓄する。つまり、クニをつくるということはコメをつくるということであり、コメをつくるということは、必然的に争いを生み、交渉を生み、協働を生むのではあるまいか。

展覧会のタイトル「Back to square one」は、「蛇とはしご」という主に欧米で古くから親しまれている子供向けのすごろくの名称を用いている。蛇はイネを荒らすカエルやネズミを食べることから神聖化された。神社に飾られるしめ縄は蛇の表象であるとする説もある。「振り出しに戻る」という意味でも用いられるこのすごろくは、碁盤の目に蛇と梯子が配置されて、コマがはしごに止まれば登って先に進むことができ、蛇の頭にとまれば尾の位置まで戻らなければならない。淡々とさいの目に応じてコマを進めることもあれば、梯子をのぼって先に進むこともあり、蛇につかまり後戻りすることもある。ゴールに向かうも振出しに戻る、私の今回のKAIRにおける旅はまさにそのような行ったり来たりの連続であった。

作品は、かつて劇場として町内の娯楽の場として利用されていた寄居座の特徴を活かしながら、映像や構造物や彫刻、ドローイング、収集物などを織り交ぜながら構成されている。神話やこの地の伝承に残る様々なエピソードを想起させ、重ね合わせ、再構成したようなある種の「仮説」、あるいは私が神山滞在中に訪ねて歩き、目で見て、観察し、学び、手を動かした痕跡を追体験できるような舞台装置と言ってもいいかもしれない。

Related URL:https://x.gd/uDOz1

Documentation(video):https://youtu.be/AgMd8Eji30w